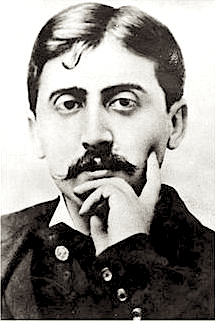

Marcel Proust (1871-1922)

[A la Recherche du Temps Perdu: The first volume of the novel purports to relate Marcel's memories of his childhood as they were brought to life for him by the taste of a madeleine dipped in tea. The madeleine reminds him of the ones he used to eat at his aunt’s house in Combray, the country town where he once spent his summers. His childhood at Combray is unhappy; his sole comfort is Mamma's good-night kiss. When dinner guests come, he does not receive this kiss. The most frequent visitor is M. Swann. On one occasion, Marcel is sent to his room before dinner ends, and Mamma rebuffs his attempt to kiss her. He decides to wait up for her and meets her in the hallway. Father sees that his son is unhappy and sends Mamma to sleep in his room and comfort him. Swann meets Odette de Crecy who introduces him to the Verdurin salon. They have a long flirtation. Swann becomes suspicious when he hears rumors about Odette and is jealous of every man she meets. His jealousy foreshadows Marcel's struggles in love and social life. Succeeding volumes culminate with Marcel finally able to write the novel.]

The Writer

During his early career Proust was not particularly creative, but he was very good at imitation both in literature and in action and speech. In 1896 he published his first book, Les Plaisirs et les Jours. The title caricatures Hesiod's Works and Days. Les Plaisirs et les Jours contains a skilful pastiche of Flaubert's style. It is a minor work. One can tell from the tone of Anatole France’s preface that he was not very interested or impressed.

A few years later Proust published a pastiche which imitated Saint-Simon. Saint-Simon recorded all the gossip and happenings of the court of Louis XIV. He was a superficial observer, interpreting petty court occurrences as the cause of great historical events. Proust saw himself as something like a Saint-Simon of the Paris salons. Like Saint-Simon’s court, the salons were completely closed in on themselves and their smallest happenings were magnified in the eyes of their members. But Saint-Simon did not have the distance on the situation which enabled Proust to see the tragic grotesqueness of it all. Unlike Saint-Simon Proust is no longer snobbish in A la Recherche du Temps Perdu, and is even more lucid than his readers. We can laugh at Saint-Simon but not at Proust.

Ruskin’s art criticism displayed a kind of pseudo-medieval romanticism. His writings on gothic cathedrals are purely aesthetic. Proust translated some of his works, but he went beyond the effeminate aestheticism of Ruskin. Proust was very cultured and well acquainted with classical French literature. The decadent influence on him was counterbalanced by the influence of his mother who loved the French classics. This sober, classical aspect of his work contrasts with the precious, decadent aspect.

Proust was always able to write in an arty way, but in A la Recherche du Temps Perdu and afterwards he no longer had so little to say that he wrote for words instead of wisdom. Scott Moncrieff’s English translation emphasizes the aesthetic, arty, and precious but in reality Proust was a classical writer who transcended this literary fashion. Moncrief knew this but his translation brought Proust back to a certain extent to his decadent symbolist origins. Despite this weakness, the translation is very beautiful and is even considered to be a work of art in its own right.

Shortly before 1900 Proust wrote, but never published, Jean Santeuil. It was a first sketch for A la Recherche du Temps Perdu which was published in 1913. Jean Santeuil was written in the third person and has many of the same themes as the later novel but it lacks the objectivity Proust brought to that work. At the end of A la Recherche du Temps Perdu the hero turns into a writer and begins to write the novel we have just finished, but in it there is no reference to anything like Jean Santeuil. Clearly, Proust considered it a failure.

Early Influences

Understanding Proust helps in understanding the Marcel of the novel and vice versa. Proust was born in 1871, the eldest son. There was another son who does not appear in the book. Proust came from a bourgeois family in good circumstances. His father, who worked in the Ministry of Health, was Catholic and his mother Jewish. His father's family lived at the Combray of A la Recherche du Temps Perdu. The first volume is built essentially on memories of vacations passed at Combray.

Proust loved his mother, but not his father. This comes out in his criticism of his father's bourgeois outlook. He says that his mother does not look carefully at her husband to discover the secret of his superiority, implying that the secret does not exist.

Proust was a sickly child cared for most carefully by his family. He had asthma at an early age. Many psychologists think that asthma is psychosomatic and indicates an inability to live alone, a kind of suppressed call to others. He had a great need of his mother.

It was a catastrophe when his parents broke their “law” for him and let his mother sleep in his room. By this act he was recognized as abnormal, as without will-power. His acceptance in the family at the expense of its law contaminated it with his sickness. This scene corresponds to something very profound in Proust’s life, repeated in other forms throughout the work. It is the cause of the feeling of exclusion and the anguish at weakness, the begging for acceptance, the social climbing, and so on. The destruction of the prestige of his family in his own eyes caused Proust to look outside for a new acceptance. He was condemned to worship and seek acceptance from those who rejected him.

The essential Proustian situation is that of the eternal outsider in any new social situation which embodies law and prestige. He tries to penetrate to the inside, to those whom he loves. All his agonies with snobs, social conflicts and love affairs were repetitions of the "scène du baiser refusé." But even acceptance could not make him happy since it simply broke the law again.

As long as Proust/Marcel was a failure, that before which he failed retained its value. Once he attained something he found it worthless. He always felt persecuted before his gods. He was a masochist because he desired only what he could not possess, what resisted him. When he was successful he put himself in the place of the "successes" whom he admired and then treated others sadistically as he felt they treated him.

Already as a child Proust had very difficult relations with other children. His search for acceptance is revealed in his letters from school at 10 years of age. In these early letters he has a Dostoyevskian “underground” attitude toward his situation. He was always fascinated by those who were as different from him as possible and who despised him. Imagine “le petit Marcel” jealous of the sportsmen in his class.

Proust was an excellent student. He used his gifts to achieve acceptance. He was a brilliant conversationalist and quickly obtained intellectual friends older than himself. For example, he became a friend of Alfonse Daudet's family. But he was not expected to go very far because of his hypochondria and laziness.

Combray

The first image of Combray is a circle, not a physical circle, but a spiritual one. Everyone in Proust belongs to a more or less open or closed spiritual circle. The society of Combray is closed, but less so than that of the highly self-conscious Verdurins. Proust’s novel is located in a place from which circles can be seen from the outside and understood.

Images from the New Testament appear often with respect to things in Combray. Like the Pope of Combray, the great aunt is at the center of its circular world. The spiritual meaning of Combray is presented from her point of view. For her circle her room corresponds to the church tower at the center of the village. She is immobile in her bed and everyone revolves around her. There is a similarity between her and Proust himself as he wrote his book, both being immobilized and both extremely curious about the tiniest facts.

Combray represents a certain type of collective subjectivity. Its ideas and attitudes structure the perceptions and thoughts of its inhabitants. This little world looks out on the rest of the world whose laws escape it. The two sounds of the door bell at Combray, one for strangers, one for family, symbolize its difference from other similarly closed circles. But it is most truly itself when it does not even notice how differently it sees things from others.

Even within Combray there are little islands, little circles incapable of communicating. The result of their encounters is often comic. When Marcel’s aunt finds out that Swann has aristocratic connections she interprets this as his misfortune, so much does she take for granted the enclosure of the bourgeoisie on itself. This story reveals the solipsism and censorship which protects Combray from dangerous ideas.

Marcel leaves Combray when he no longer believes the things which condition the views of the people there. His memories of it resemble an anthropological field study of bourgeois primitivism.

The Fall

Marcel’s fall from his paradise in Combray is prefaced by the scene of the refused kiss. That was the traumatic experience, the psychological motive behind everything that follows. Thus the fall is already present in Combray. But the memories called up by the madeleine also recover the happy side of Combray.

Belief in Combray is eventually shattered by Mlle. Vinteuil and homosexuality or sexuality in general and by Legrandin’s snobbery. These things force Marcel out of Combray to find another inner circle beyond that of his childhood. But this poses problems for Marcel as it had in Proust’s own life.

Proust was half Jewish, half Catholic and bourgeois, yet he felt outside of Judaism, Catholicism and the bourgeoisie. Mme. Strauss hosted a bourgeois salon to which he was admitted, a first victory over exclusion. Her salon corresponds to the Verdurin salon of the book. It gathered artists, intellectuals and bourgeois rather than aristocrats. When he was accepted there he tried to get into the aristocratic salons, not because they were more interesting, but because they were closed to him.

While Marcel was trying to gain entry into the inner circle of the aristocratic Guermantes, he had the experience of the madeleine and realized that the real inner circle was his protected childhood at Combray. After leaving Combray, the whole book is a long fall, everything becoming worse and worse till Sodome et Gomorrhe. He finally finds himself in Le Temps Retrouvé and renounces his earlier life.

The Aristocracy

After his father broke the family's law Proust went looking for a new God that would be inflexible and perfect, that would incarnate the opposite of his family. This was the aristocracy. Similarly, Marcel’s loves and his aspirations for social advancement are motivated by the desire for some new infinitely beautiful world in which he will become a new person. He loved Mme. Guermantes for the social and sexual hopes for a new life that he found in her. She was a kind of goddess for Marcel.

There is a description of Marcel watching the Guermantes in their box in the theatre. They appear to be underwater because of the light. Marcel’s desire divinizes them as gods of the water and the ocean. Like Neptune, they are of another element. They inhabit a box, a circle which is closed to him.

After many failures Marcel succeeded in getting into the Guermantes’ salon and this devalued it too. In this we see the metaphysical aspect of Proustian desire. For Proust before his novelistic "conversion" all paradises are lost or unattainable.

Psychological Laws

Proust claimed that there were psychological laws controlling all the characters in his book. He believed that all desire was the desire to be. At the level of physical need people are materialists, but beyond this level desire is spiritual, with no real object at all. We want things for psychological motives instead of for what they are in themselves.

Proust's psychology is revealed in Swann's love, which is confounded with his snobbery. Swann did not desire Odette in herself but only falls in love with her when she is lost to him. This is linked to Swann's attraction to the Verdurins. He loved Odette because of the obstacle to her they represented. He would not have loved her if she had been on a desert island (or married to him). Swann later marries Odette to prove to himself that he does not love her, or to destroy his love.

Jealousy in love and snobbery are equivalent. In the conflict between Forcheville and Swann for Odette, each acted as an obstacle to the other and therefore reinforced the other's desires and his own self-doubts. Snobbery works the same way. Marcel later desires to be Charlus, not because of what Charlus is, but because of the obstacle represented by the salon to which he belongs. Proustian masochism grants all the prestige and value to the obstacle that creates and blocks his desires.

The pursuit of the opposite, the extreme, appears in many of the characters. All Swann’s early loves were for the peasants and poor people he desired to be. He loved Odette because he was a socialite and she was nothing. Similarly, the women Marcel loves are all his opposite, insensitive and unintellectual.

Proust demystifies snobbery by showing that people live in totally abstract and nonexistent worlds. He was capable of seeing this in his own life and concluded that it was a universal condition, but he did not understand its historical character and its sociological causes in the nature of democracy. He might have found the connection in de Tocqueville.

Snobbery

Proust shows that even the aristocracy is governed by psychological laws. There are no real class distinctions. The difference between the Guermantes and the Verdurins is entirely abstract. The more abstract the difference becomes, the more the enemies are the same, the more intense are their conflicts. Racism is a good example of this.

Proust understood that only near equals can experience snobbery and conflicts of vanity. Only snobs can hate snobs since only snobs are troubled by each other’s snobbery. The comparison of Françoise with the Verdurins shows this clearly. All the characters are provincial in a sense but Françoise is the most provincial. She is so absorbed by the circle of Combray that she has no ability to see herself in comparison to others and so is incapable of snobbery.

The salons are a kind of artificial caricature of Combray. Mme. Verdurin is compared with a medieval ruler demanding absolute loyalty because she has so little self-confidence and is so wounded by the Guermantes’ snobbery. Her salon can only exist in opposition to theirs. But Combray does not oppose itself to anything. Patriotism can exist there while in the salons one finds only nationalism and totalitarianism.

Proust’s criticism of the Verdurins is much crueller than his criticism of the Guermantes because they are contrasted with the ordinary middle-class respectability of Combray which possesses a certain naive authenticity. But the Verdurins pretend to be devoted to art, intelligence, spiritual values when actually their only god is the Guermantes.

Although there is much bitterness in Proust's critique of the Verdurins he is far more objective in including Swann in their sickness than he was in Jean Santeuil. In that book, a sort of study for A la Recherche du Temps Perdu, good and evil characters are so different that neither is properly represented. The hero is absolutely innocent and is slandered by others. This is the view from inside one provincial social circle, not the synoptic view of the later novel. By reaching so deeply into the provincialism of its characters A la Recherche du Temps Perdu transcends their provincialism.

Epistemology

The image of the magic lantern in the overture resembles consciousness projecting like a camera from within its circle. It is the image of Marcel, trapped by an inescapable vision of the world. What we project onto the object is the most important part of our knowledge. Proust shows the unity of subject and object in the Weltanschaung of the individuals.

Proust’s depiction of subjectivism is in the interest of an objective view, an implied knowledge of what things are really like. People refuse to see what is right before their eyes but which does not fit into their picture of the world. This is a kind of self-censorship which the novel, as a realistic genre, must transcend. Proust presents these epistemological ideas novelistically rather than theoretically.

The novel requires a combination of internal perception and a later exterior view. For Proust truth lies in this interior--exterior view of memory which alone can possess the past. A pure outside observer would miss a great deal as do those on the inside. Proust’s act of memory is a spiritual experience which grants him true knowledge.

Proust wrote the whole of A la Recherche du Temps Perdu from the point of view of the end and in fact the last volume was written first. In Le Temps Retrouvé Marcel has another much more intense experience similar to that with the madeleine. It is this experience which converts him into a novelist. These scenes show us that there are two points of view in the book: that of the older man who lived through everything and wrote the book and that of Marcel the character as he approaches that state from one fall to the next. The book shows both the character Marcel, developing into the writer of the novel, and the man Proust who sees everything from beyond.

Proust’s Greatness

The essential problem of the modern writer is the difficulty of communication. Some writers try to depict the lack of communication, but the greatest join and transcend opposed visions of the world. In this respect Proust’s novel is unlike an abstract work such as L'Etranger which asserts the absolute impossibility of communication. Proust was not just reporting on the social situation. He tried to reveal the essence of communication and to understand the failure to communicate. Like Balzac he does what none of his characters could do in showing the relations between individuals and groups that are closed in on themselves. He shows concretely why communication is nearly impossible and in so doing helps to establish it.

A good novelist has to see himself in others and others in himself. Proust had to live and suffer his snobbery and come to an understanding of it before he could create the work of art that liberated him from it. The whole society had Proust's sickness to a certain extent, but he had it more and therefore lived it more deeply and painfully, and was finally able to master it. He understood the vanity and irrationality of his desires and in Le Temps Retrouvé he transcends them.

Proust’s suffering and illusions ultimately result in his triumph. His insight gave rise to an aesthetic dynamism which saved him through his devotion to art. But this was not the aestheticism of those who make the work of art into a lovely ornament. Art was truly something from the beyond. Proust's failure as a man was the source of his greatness as an artist, and his creation gave his life value in the end.